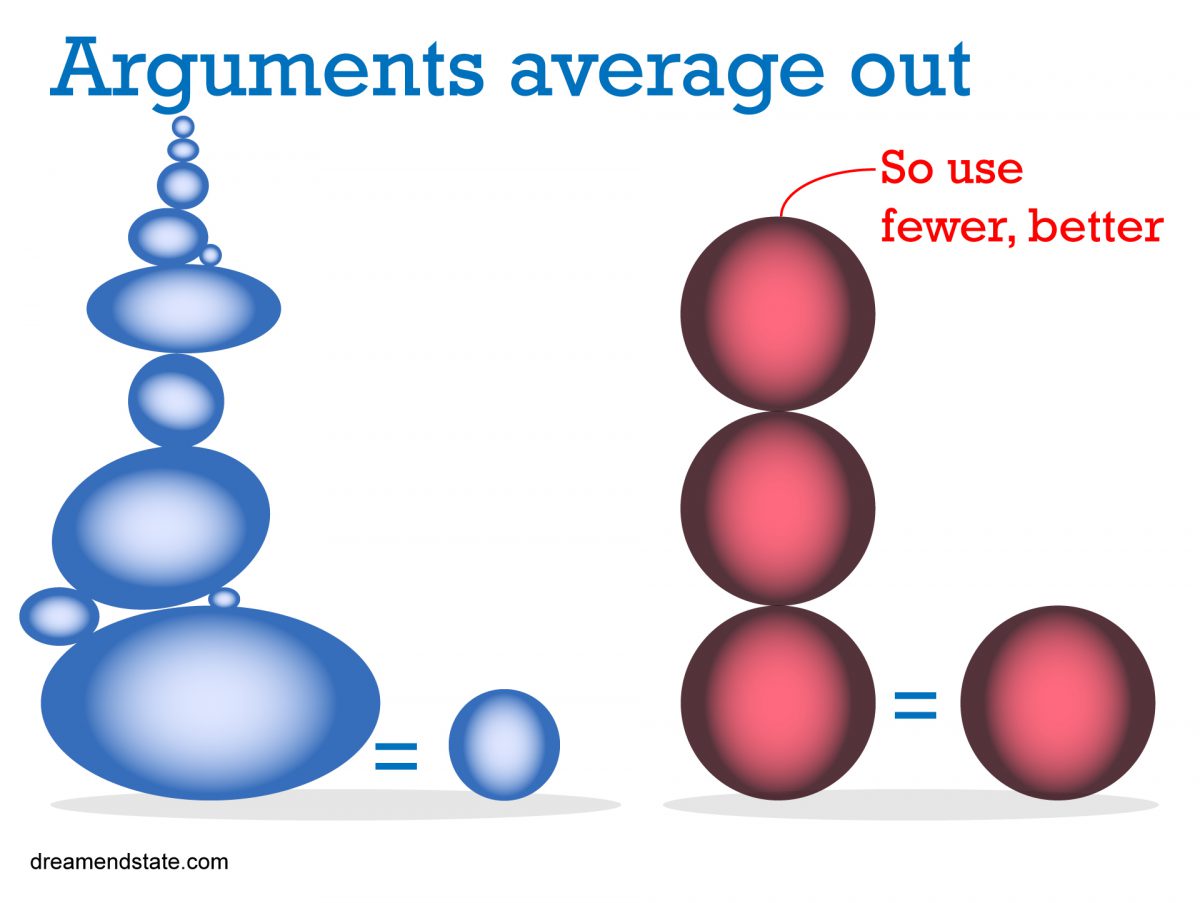

What’s the best way to win an argument? If you think it’s by coming up with as many reasons why you’re right as you can, you’re wrong.

This seems counterintuitive at first. Surely the way to make a case stronger is by adding more arguments in favour? But the person you’re trying to convince doesn’t see your arguments adding up — they see them averaging out. If you have a strong argument and then add some more supporting points that aren’t as convincing, you’re weakening your case.

In an experiment by Christopher Hsee, one group of people was asked how much they would pay for a brand-new 24-piece dinnerware set, while another was asked how much they would pay for a 40-piece set, which had more brand-new items than the smaller set but also included a few broken items. The result was that the smaller set was judged to be worth more than the bigger set. By adding a few inferior items, the seller weakened the overall proposition for buying the product.

Niro Sivanathan found that people react in the same way when dealing with arguments against doing something. Drugs that are advertised in the US as having side effects of “heart disease and stroke” are judged to be more risky than those advertised as having side effects of “heart disease, stroke, headache and dry mouth”. The major and minor risks are averaged out, so the drug with more side effects is seen as less risky.

This matters not just for advertisers, but for anyone who is trying to persuade someone. A CV with a few strong arguments for why you should get the job looks better than one with all the arguments. And a three-word slogan is more effective at winning an election than 105 pages of policies. The quality of arguments, and how they’re delivered, are more important than the quantity of arguments.

Watch out for

This dilution effect not only shows how to make arguments more convincing, but also affects how people make judgements in a variety of situations. People given a mix of relevant and irrelevant information about an individual come to less extreme conclusions than people given only the relevant information, helping to reduce the effect of stereotypes.

With thanks to Ivan Edwards who wrote most of this post. Thanks Ivan!

Resources

Hsee, Christopher K. (1998), Less is Better: When Low-Value Options are Valued More Highly than High-Value Options, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, pages 107-121

Nisbett, Richard E.; Zukier, Henry & Lemley, Ronald E. (1981), The Dilution Effect: Nondiagnostic Information Weakens the Implications of Diagnostic Information, Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 13, pages 248-277

Sivanathan, Niro (May 2019), The counterintuitive way to be more persuasive , TED

Sivanathan, Niro & Kakkar, Hemant (February 2019), How Drug Company Ads Downplay Risks, Scientific American