This model explains why some large, established firms respond well to largescale disruption, while others struggle.

Imagine you run a chain of clothes shops. You sell the coolest, most popular clothes and you’re the king of the High Street, with a knighthood to boot. But a new generation of online retailers appears. You start your own website to combat the threat, but slowly your customers slip away, your shops close down and the challengers pick away at the carcass of your dying empire. Why couldn’t you, as the incumbent and dominant player in the industry, adapt to the change in the market?

And why do incumbent businesses fail in the face of major external challenges, even as their managers try everything to stay on top? That’s what Clark Gilbert attempted to solve with his model on inertia.

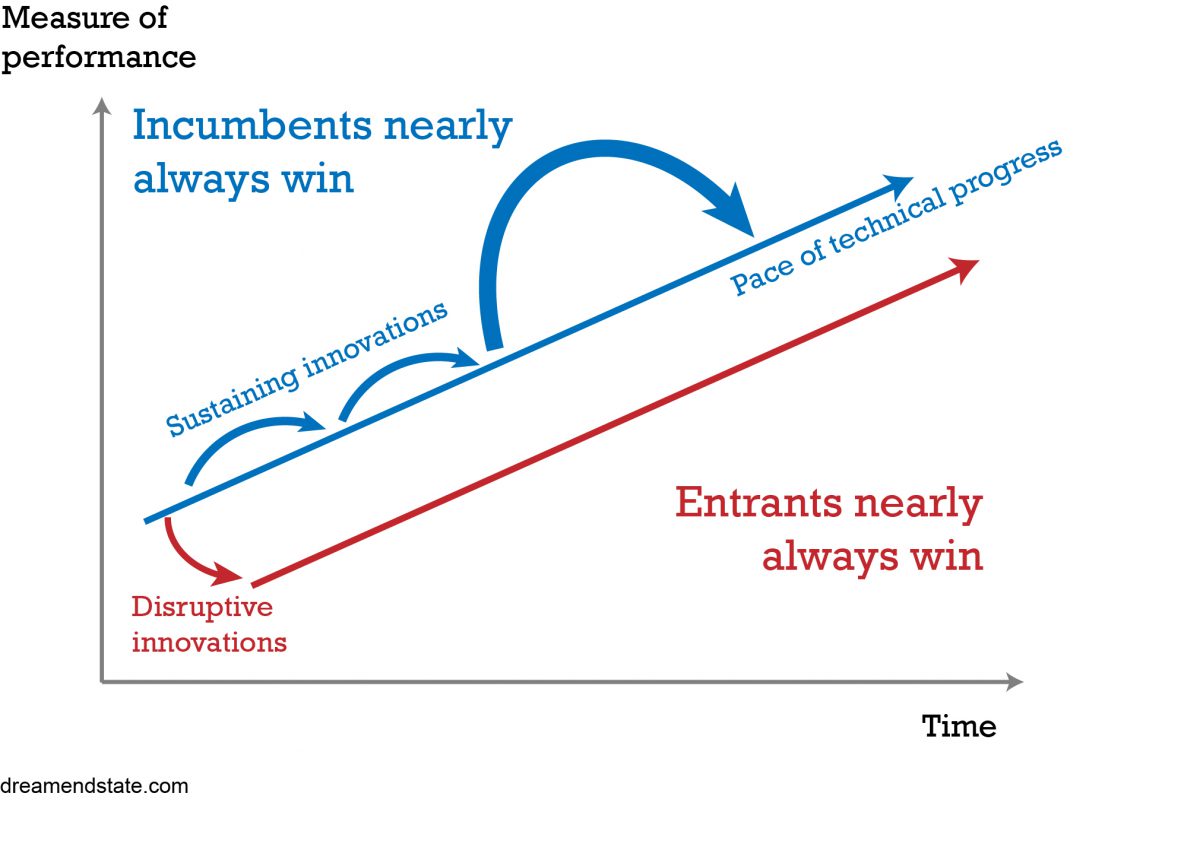

To understand the problem, he defined inertia as coming in two different forms — an unwillingness to invest (resource rigidity) and an unwillingness to change the way the business operates (routine rigidity). The first form is easy to overcome. Tell a manager that a new threat will put them out of business, and they’re usually happy to throw money at the problem.

The trouble is this causes an increase in the second form of inertia. Now they’ve committed extra resources, the manager wants to use tried-and-tested methods, to control how every penny is spent — and they certainly don’t want to take any risks.

Here are Gilbert’s three steps to overcome routine rigidity.

- Bring in outside influence

If you’re a clothes shop setting up a website, put the digital marketers and social media experts in charge of what it should look like. If you put the old guard in charge, inevitably it won’t be a new product — it will be an extension of the old business, facing the same problems. - Separate the new venture

The new venture should operate independently, with its own management, its own processes and business model. Maybe it will even have a different name and a separate office. - See opportunities, not threats

Now that the new venture is separated from the parent business, its managers won’t see the rise of online shopping as an existential threat — they’ll see opportunities to reach new audiences, sell niche products and cut overheads.

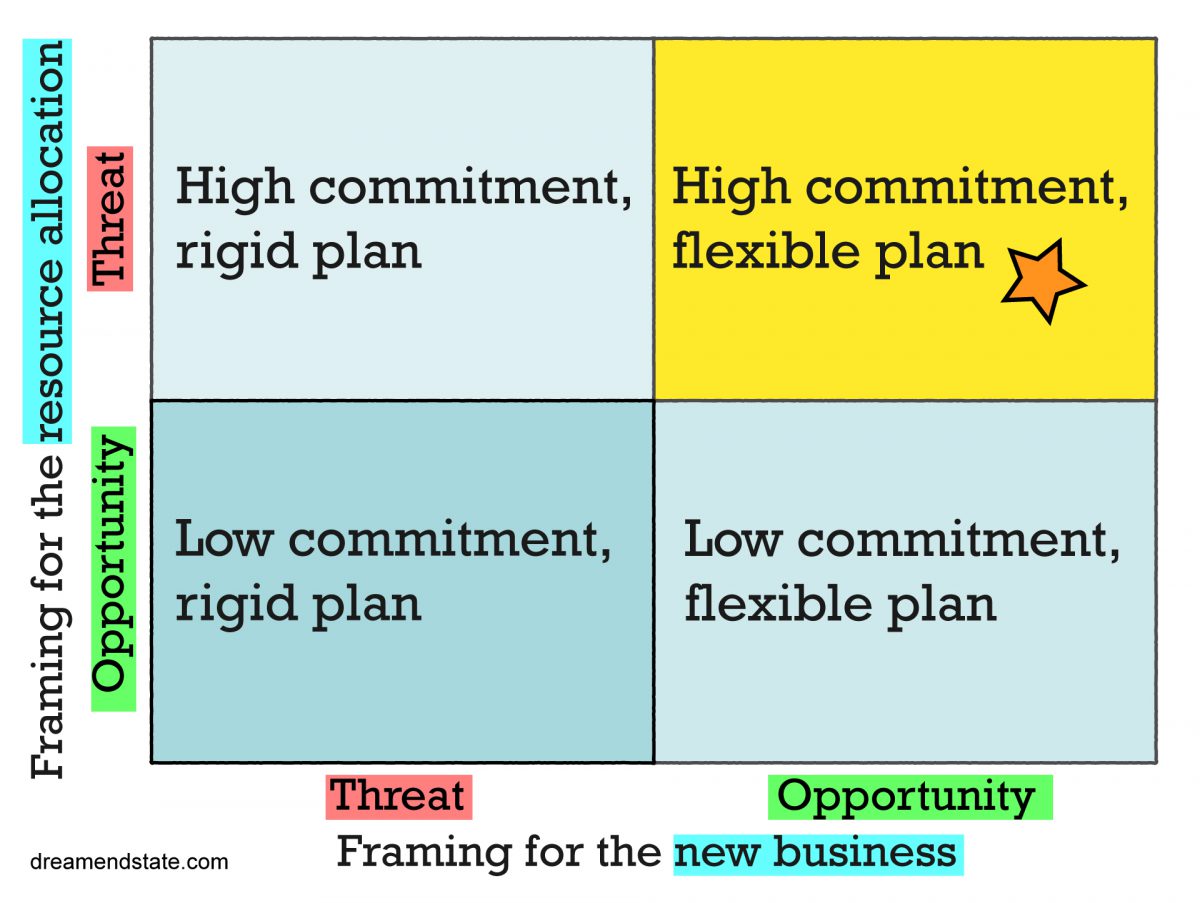

The disruption is best framed as a threat within the resource allocation process in order to garner adequate resources. But once the investment commitment has been made, those engaged in venture building must see only upside opportunity to create new growth. Otherwise, they will find themselves with a dangerous lack of flexibility or commitment.

Christensen & Raynor, pp.114-115, The Innovator’s Solution (2013)

Watch out for

Why is it harder to overcome routine rigidity? The answer may lie in another model, prospect theory . This holds that the pain of a loss is greater than the pleasure of a win. Inertia over the use of resources is motivated by the fear of losing what you have — if you don’t devote resources to this threat, you’ll go out of business. But changing a business model to perceive opportunities rather than threats requires risk-taking and motivation by the prospect of gains.

With thanks to Ivan Edwards who wrote most of this post. Thanks Ivan!

Resources

Christensen. C. & Raynor, M. (2013). Innovator’s Solution, Revised and Expanded: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Harvard Business Review Press

Gilbert, Clark G. (Oct. 2005), Unbundling the Structure of Inertia: Resource Versus Routine Rigidity, Academy of Management Journal

Gilbert, Clark G. (2002), Can competing frames coexist? The paradox of threatened response, Working paper 02-056, Harvard Business School