This is how a group of people can solve a problem without arguments.

Think about all the times you’ve been in a team meeting, dealing with some issue. Everyone goes in with the best intentions, but the team members quickly form their own ideas of what needs to be done, argue about why everyone else is wrong, then eventually go with whoever won over the most (or shouted the loudest).

The six thinking hats are a more efficient way of solving problems than arguing. In an argument, each side picks a conclusion, finds evidence to support it, and ignores or discredits any evidence to the contrary. Emotions take hold as each side aims for the glory of being right and the thrill of defeating an adversary. It sounds like a terrible way to solve problems constructively. Yet our entire political and legal systems are based on it.

The alternative to arguments is ‘parallel thinking’. Instead of each individual taking different sides, all individuals take the same side and look in the same direction, in any one moment.

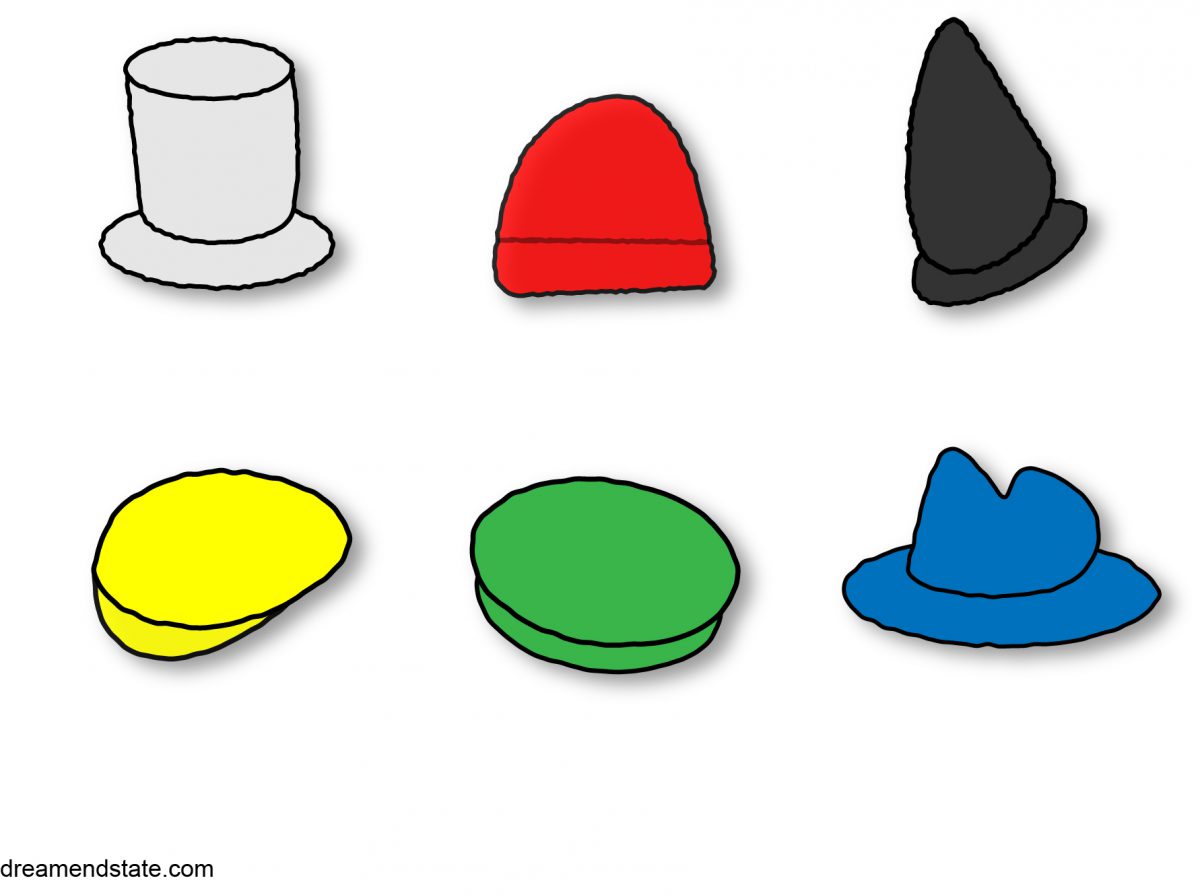

That’s where the imaginary hats come in. Each hat is a way of looking at an issue. They come in pairs, but you can only wear one at a time. And in a group discussion, everyone wears the same hat at the same time.

White Hat and Red Hat

The white hat is where the team establishes what information is known and what information is needed. This is about facts – not interpretations, judgements or opinions.

“Market research shows demand for coffee flavour biscuits is growing.”

The red hat is where intuition, feeling, opinions and emotion come in. They can be based on experience or just a hunch.

“I feel our current range of biscuits is boring and old-fashioned.”

Black Hat and Yellow Hat

The black hat is about caution and critical thinking. Everyone should be looking for danger signs, something that could go wrong.

“If we introduce a coffee flavour biscuit, our rival might copy us.”

The yellow hat is about sunny optimism. Finding possibilities for putting a plan into practice, and searching for the benefits.

“If our rival copies us, that could help grow the whole market so we’ll still benefit.”

Green Hat and Blue Hat

The green hat is about being creative. Coming up with new ideas, options and ways of looking at things.

“How about adding chocolate chips to the biscuits?”

The blue hat is about control and discipline. It ensures the meeting remains structured rather than free-flowing (which will probably deteriorate into an argument), and as a result the leader of the meeting wears the blue hat at all times. The discussion may start and end with everyone wearing the blue hat, first to define the problem and lastly to make a decision.

“We’ve agreed the next step is to develop a coffee flavour chocolate chip biscuit.”

Watch out for

While some tests and teamwork models assign people to different categories based on their strengths, De Bono says this restricts them rather than getting the best out of them. The advantage of the six hats is everyone tries a bit of everything, and comes up with ideas no-one else would’ve thought of.

“There is a huge temptation to use the hats to describe and categorize people, such as ‘she is black hat’ or ‘he is a green-hat person’. That temptation must be resisted.”

Edward de Bono, Six Thinking Hats, p. 6

Did you know? De Bono coined the phrase “lateral thinking.”

With thanks to Ivan Edwards who wrote most of this post. Thanks Ivan!

Resources

De Bono, Edward (1985), Six Thinking Hats, 2016 edition, Penguin Life