The experience of the user should be the most important consideration when designing a product.

Sound obvious? You’d be surprised. Look around the room you’re sitting in now and you’ll probably find something that’s been badly designed. Maybe a remote control with lots of buttons whose purpose is a complete mystery. Or a website that makes it impossible to find the information you need. (Please tell us if it’s this website.)

Don Norman set out the problems with how things are designed in The Design of Everyday Things, first published in 1988. Since then, an entire industry of user-experience (UX) designers has cropped up.

He argued that, even though most designers think they’re making things better for the people who will use their products, in reality, they have no idea how people use them. So they design things how they want them to be, perhaps adding lots of clever features, or making them look like a beautiful work of art that will win them a prize.

But users shouldn’t have to adapt themselves to work out how to use a product. Instead, the product should be adapted to the user, so he doesn’t even have to think about how to use it. When you walk up to a door, you should just know whether it’s a push or a pull door. If you have to read a little sign saying ‘pull’, that’s bad design. If you guess wrong and push, that’s the designer’s fault, not yours.

To design things well, we have to understand how people interact with them. Here are a few things to consider when designing something – whether that’s a new product, a website, or a way of making something work.

- Mapping

The user should be able to work out in their mind what something does. A switch next to a light should turn on that light. - Affordances

How the user perceives what an item is for. A switch is for pressing, a knob is for turning. - Constraints

Make something easy to use by limiting what you can do with it. If one button does one thing, it’s hard to get that wrong. If one button does lots of things depending on how you press it, the user will make mistakes. - Feedback

When the user does an action, they should get a signal that the action had a result. If you press a button and nothing happens, you’ll probably keep pressing it. If you press a button and a light comes on, you’ll know it works.

Watch out for

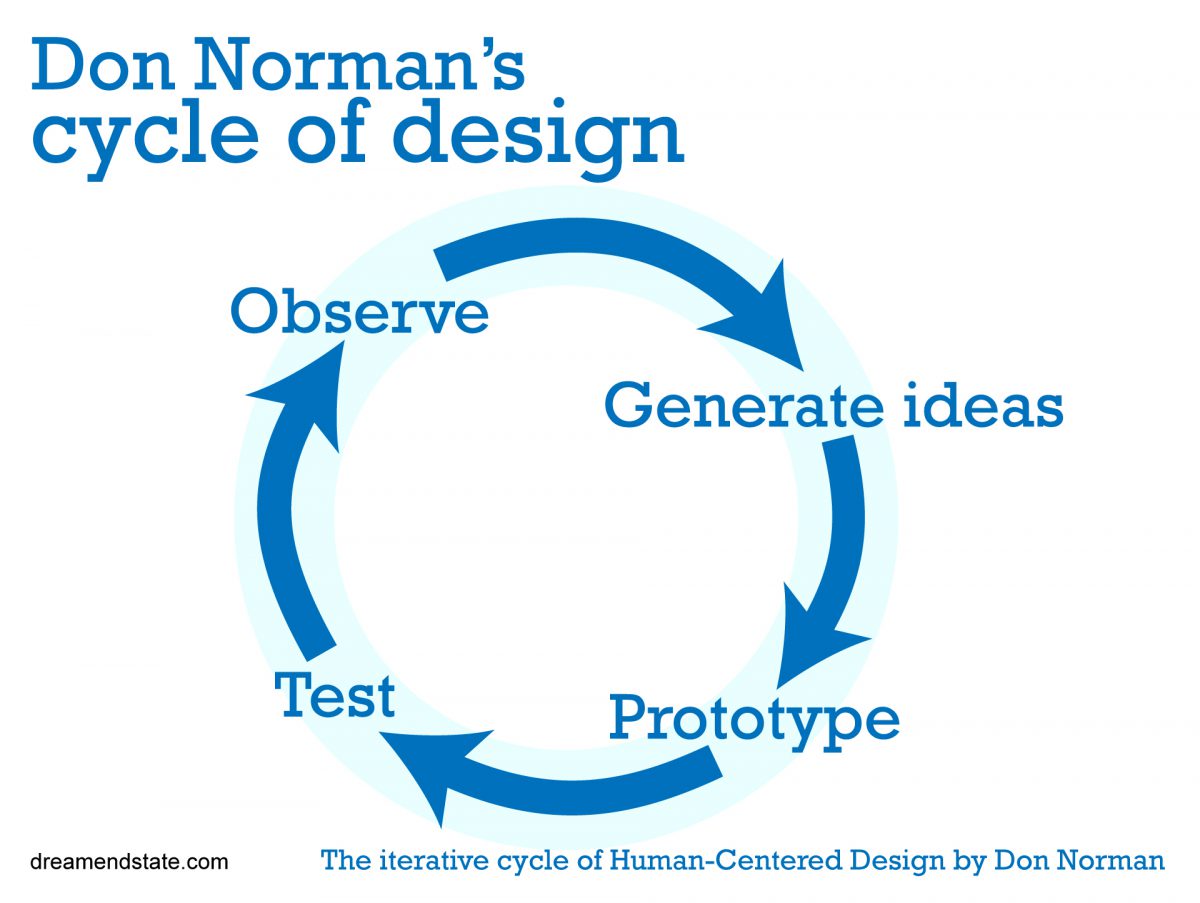

Even after you think you’ve created a great user-centered design, the only way to find out is through research and testing. Create a prototype and observe how a sample of people use it. Or if you’re making a big purchase, try it out as much as possible first. You may be surprised by the problems that come up.

User-centered design thinking dovetails with some of the core characteristics that make up great innovators: understanding from first principles the “job to be done” by always questioning conventional wisdom and the status quo and observing the behaviour of customers to figure out new ways of doing things. See the Innovator’s DNA model.

With thanks to Ivan Edwards who wrote most of this post. Thanks Ivan!

Resources

Don Norman on the term “UX” (July 2016), Nielsen Norman Group

Norman, Don. (1988), The Design of Everyday Things, 2002 edition, Basic Books

Stevens, Emily. (July 2019) The Fascinating History of UX Design: A Definitive Timeline, careerfoundry.com