It’s more a credo to live by rather than a mental model, but I’ve categorized it as a mental model. Sue me.

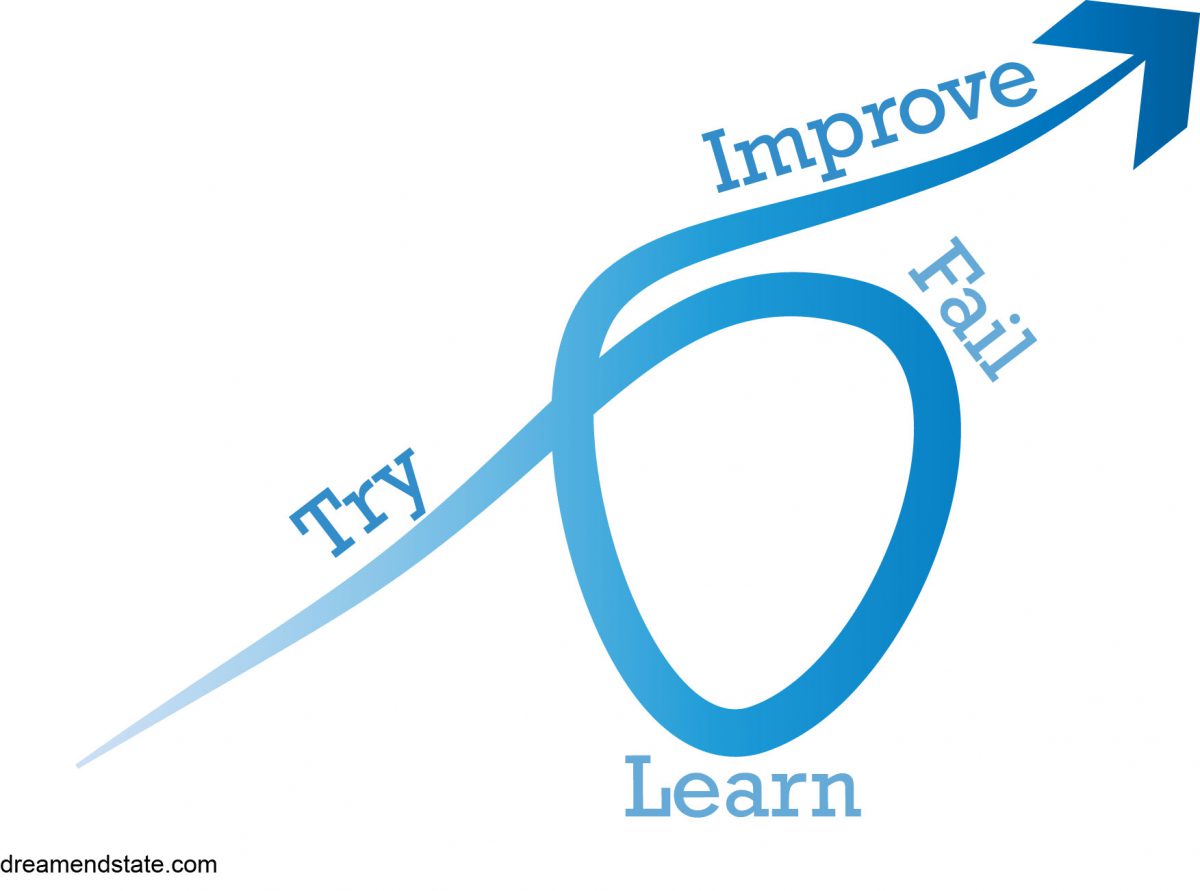

A central tenet in Ray Dalio’s Principles and beloved by Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Elon Musk and other highly successful investors and businesspeople, Always Be Learning – or ABL – is about how we learn, and how we learn from our mistakes and our failures.

I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent, but they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than they were when they got up and boy does that help, particularly when you have a long run ahead of you.

Charile T. Munger

I will write more (and more coherently) on this later. Probably.

It’s better to have tried and failed than to live life wondering what would’ve happened if I had tried.

Alfred Lord Tennyson

Watch out for

It works best with dispassionate reflection, which is easier said than done since we’re programmed to rationalize our mistakes.

It’s not about failing fast. It’s about learning fast.

Resources

Baid, G. (2020) The Joys of Compounding: The passionate pursuit of lifelong learning. Columbia University Press

Dalio, R. (2017) Principles. Simon & Schuster