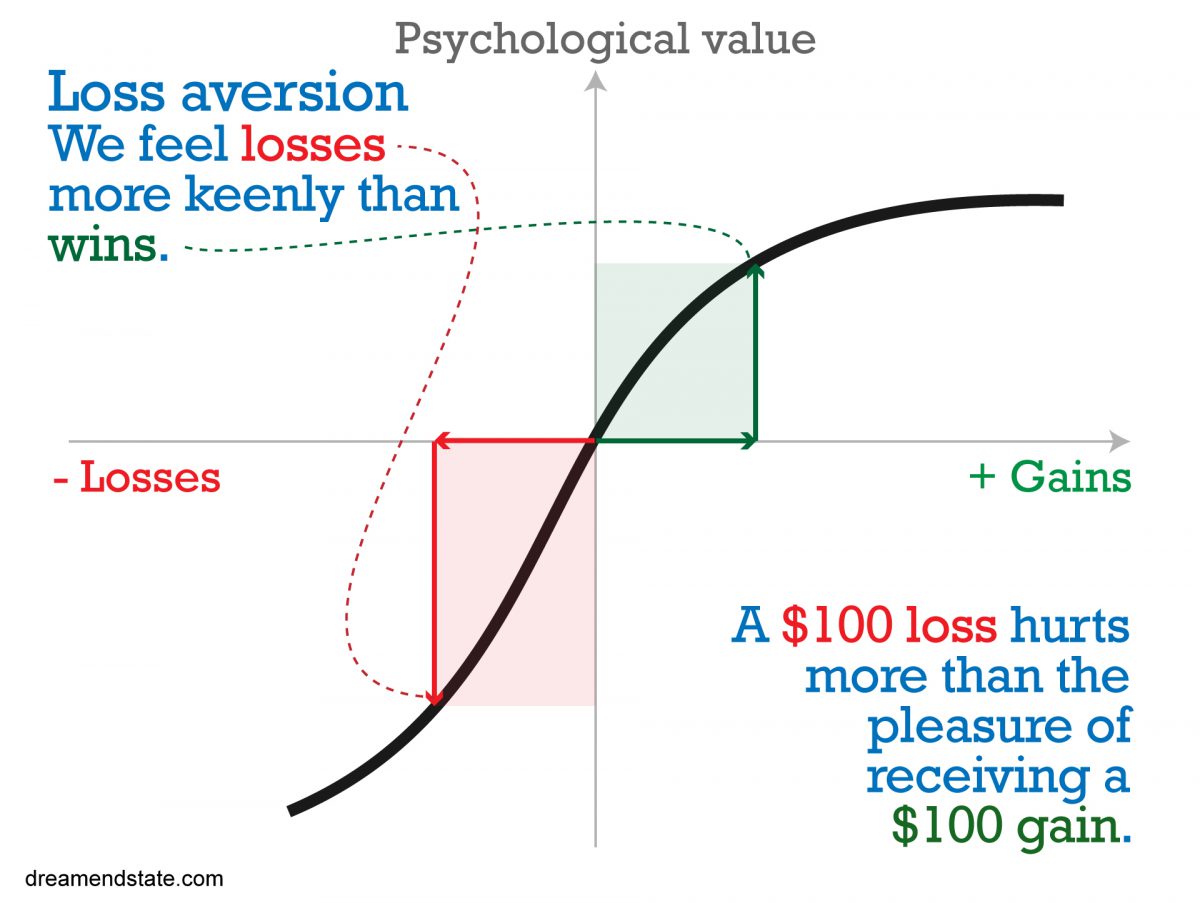

This is the model that explains loss aversion and risk-seeking when we’re losing. The famous “S” curve addresses flaws in Daniel Bernoulli’s expected utility theory that he proposed way back in 1738 – a theory which had remained unquestioned for more than two centuries until two psychologists came along in the 1970s.

Here’s a generous deal: I’ll give you a choice between a guaranteed £500, or we can toss a coin for £1000. You’d probably bank your £500. Thank you very much.

Now imagine I gave you a different deal. You can pay me £500, or we can toss a coin: either you pay me £1000 or you pay me nothing. You’d probably take your chances. Anything to wipe the smile off my face.

Each option has the same monetary value, but the decision you make is different, depending on whether you’re gaining or losing money. The reason for that lies in prospect theory. Understand this, and you can understand why people and organizations make the decisions that they do.

Prospect theory was first published by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979. It aimed to challenge the previously accepted idea that people make rational decisions based on probability and the expected utility of an outcome as explained by Bernoulli. Instead, prospect theory accommodates the different attitudes to risk we have for gains and losses. Essentially, “losses loom larger than gains.”

Bernoulii’s theory assumes that the utility of wealth is what makes people more or less happy, but it lacks a vital moving part: the reference point from which gains and losses are evaluated.

The prospects of gains and losses are what drive the decisions made by companies and their managers every day. Businesses that are performing below expectations will be reeling from the losses and turn to increasingly risky strategies to try to recover. That may lead to throwing good money after bad, like a gambler making increasingly outlandish bets at the end of a day of heavy losses.

On the other side, everyone is loss averting to some degree. Loss aversion is often heightened in business settings when managers feel there’s no room for failure. For example, a speculative investment of £1 million for a 50% chance of a £10 million return would have an expected value of £4.5 million and should be an investment that’s made by any objective standard but might be rejected by the manager because she fears losing her job if the investment fails.

You can measure the extent of your aversion to losses by asking yourself a question: what is the smallest gain that I need to balance an equal chance to lose $100? For many people the answer is about $200, twice as much as the loss. The “loss aversion ratio” has been estimated in several experiments and is usually in the range of 1.5 to 2.5. This is an average, of course; some people are much more loss averse than others.

Daniel Kahneman, p.284. Thinking, Fast and Slow (2012)

Watch out for

Whether an event is considered a gain or a loss depends on expectations rather than reality. If my share portfolio rises 10% in a year when my friend gains 20%, that will feel like a loss. If I only lose a bit of money in a market crash, that will feel like a win. This ‘reference point’ between gains and losses can change over time, or from person to person.

Kahneman states that like Bernoulli’s theory, Prospect theory has flaws of its own. Most notably, the reference point usually has a value of zero, which can lead to some absurd results. It means that winning nothing when you have a 90% chance of winning $1 million and a 10% chance of winning nothing is assigned the same value as losing when you buy a lottery ticket. Prospect theory doesn’t take into account disappointment or regret.

With thanks to Ivan Edwards who wrote most of this post. Thanks Ivan!

Resources

Bendickson, J., Solomon, S., & Fang, X. (Summer 2017), Prospect Theory: The Impact of Relative Distances, Journal of Managerial Issues

Kahneman, Daniel & Tversky, Amos (March 1979), Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk, Econometra

Kahneman, Daniel, (2012), Thinking, Fast and Slow, Penguin Books

Newell, Benjamin R.; Lagnado, David A. & Shanks, David R. (2007), Straight Choices: The Psychology of Decision Making, Psychology Press